SQL join flavors

There is more to SQL joins than you might think. Let's explore them a bit.

We'll use two simple tables: companies and jobs they offer.

There are three completely fictional companies — Hoogle, Emazon and Neta — that offer a surprisingly small number of jobs:

jobs companies

┌────────┬─────────┬──────────────┐ ┌─────────┬───────────┐

│ job_id │ comp_id │ job_name │ │ comp_id │ comp_name │

├────────┼─────────┼──────────────┤ ├─────────┼───────────┤

│ 1 │ 10 │ Data Analyst │ │ 10 │ Hoogle │

│ 2 │ 20 │ Go Developer │ │ 20 │ Emazon │

│ 3 │ 20 │ ML Engineer │ │ 30 │ Neta │

│ 4 │ 99 │ UI Designer │ └─────────┴───────────┘

└────────┴─────────┴──────────────┘

(swipe left to see the companies)

Hoogle is interested in Data analysts. Emazon is hiring Go developers and ML engineers. Neta is not hiring at all. And some unknown company with id 99 is desperately looking for a UI designer.

Now let's join!

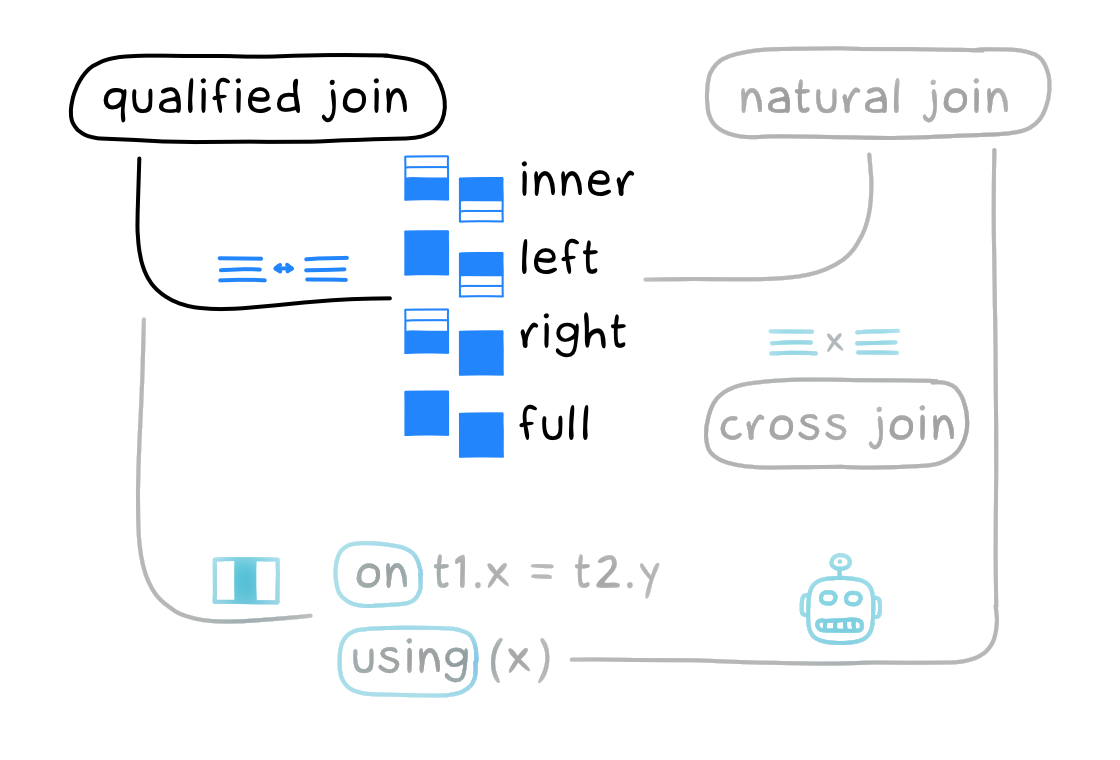

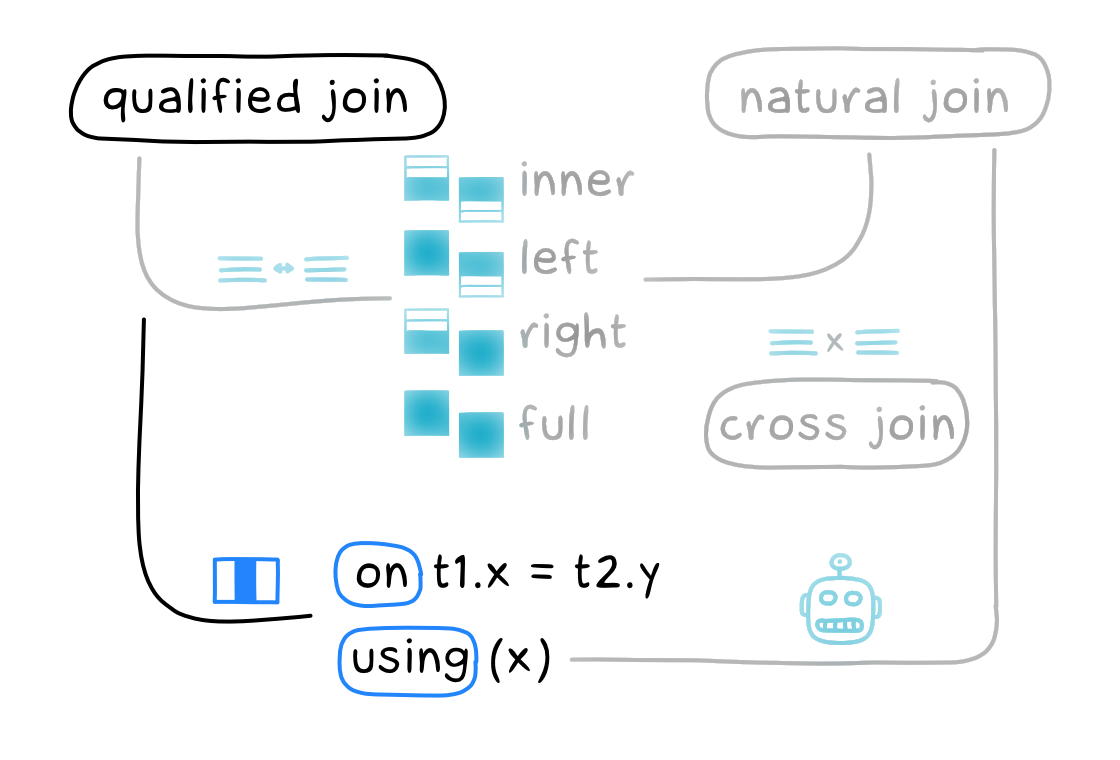

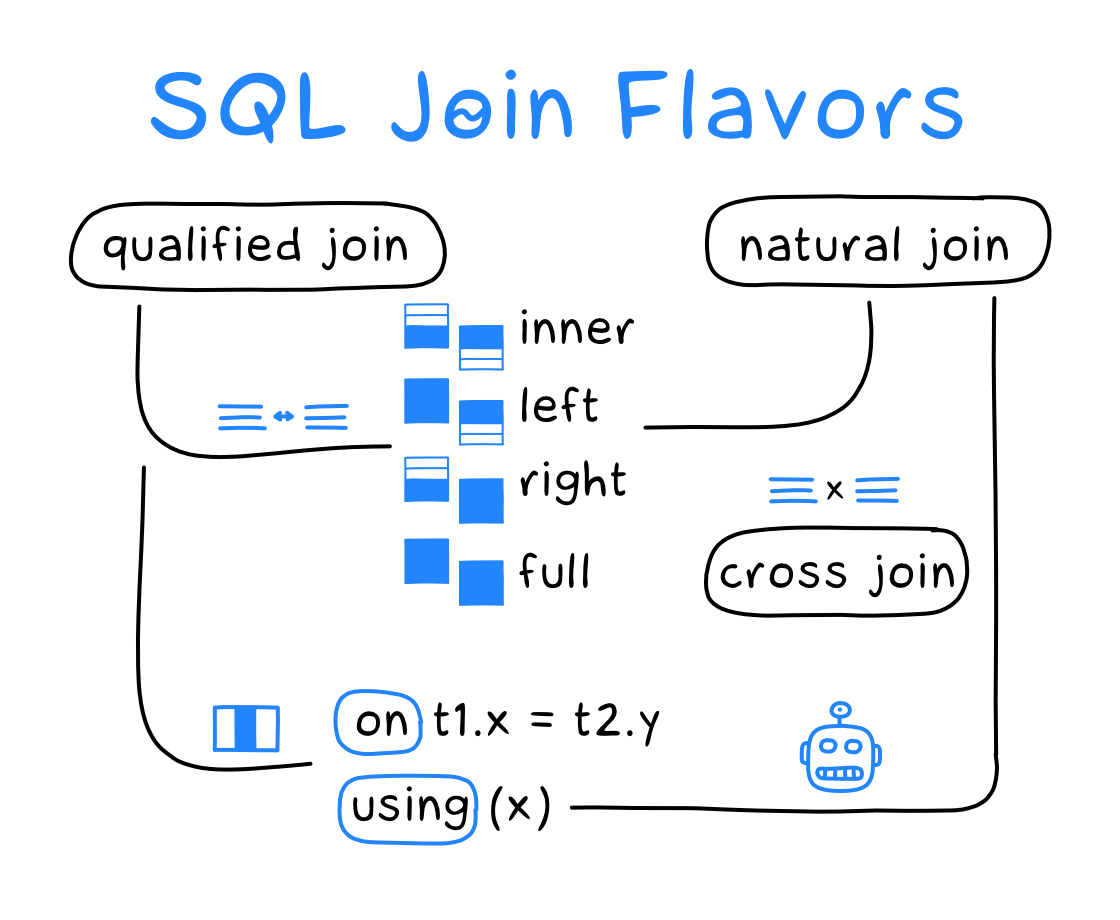

Qualified join

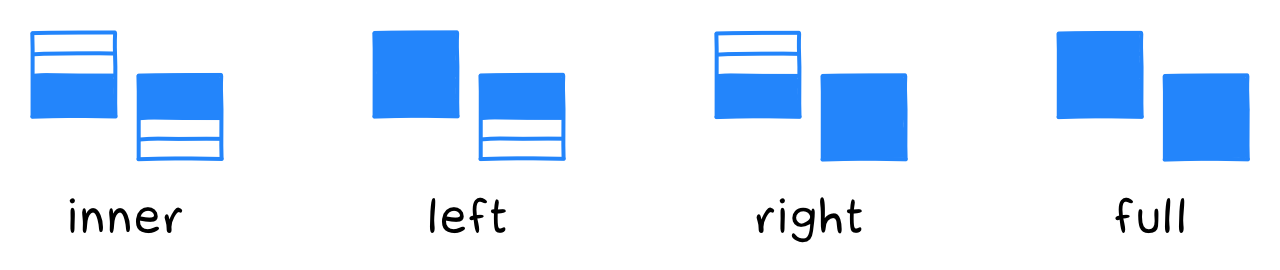

"Qualified join" is a umbrella term for the most common types of joins: inner, left, right and full. If you haven't heard of these or have forgotten what they do, I suggest you check out the SQL Cheat Sheet.

A qualified join connects records from two datasets into one, according to the matching criteria you specify. Here is how it looks like in general:

table [join-type] JOIN table join-specification

A table is not necessarily a table per se. It can be a view, a subquery, or basically any table-like structure. But we'll call it "table" for brevity.

A join-type is one of the following:

innerincludes only matching rows from both tables.leftincludes matching rows from both tables and non-matching rows from the left table.rightincludes matching rows from both tables and non-matching rows from the right table.fullincludes matching rows from both tables and non-matching rows from both tables.

There is also an optional outer keyword for left, right, and full joins, which changes nothing (as if SQL wasn't complex enough):

LEFT OUTER = LEFT

RIGHT OUTER = RIGHT

FULL OUTER = FULL

Oh, and the entire join-type can also be omitted. By default, every join is an inner join.

A join-specification defines the matching criteria. It comes in two flavors.

The first one uses the on keyword, which you've probably seen a thousand times. For example, let's select jobs with corresponding company names:

select

job_name, comp_name

from jobs

join companies on jobs.comp_id = companies.comp_id;

The second join-specification flavor is less known. It employs the using keyword and works only if the column we are joining on has the same name in both tables:

select

job_name, comp_name

from jobs

join companies using(comp_id);

While we can use any comparison operator with on, using only checks for equality.

Nice!

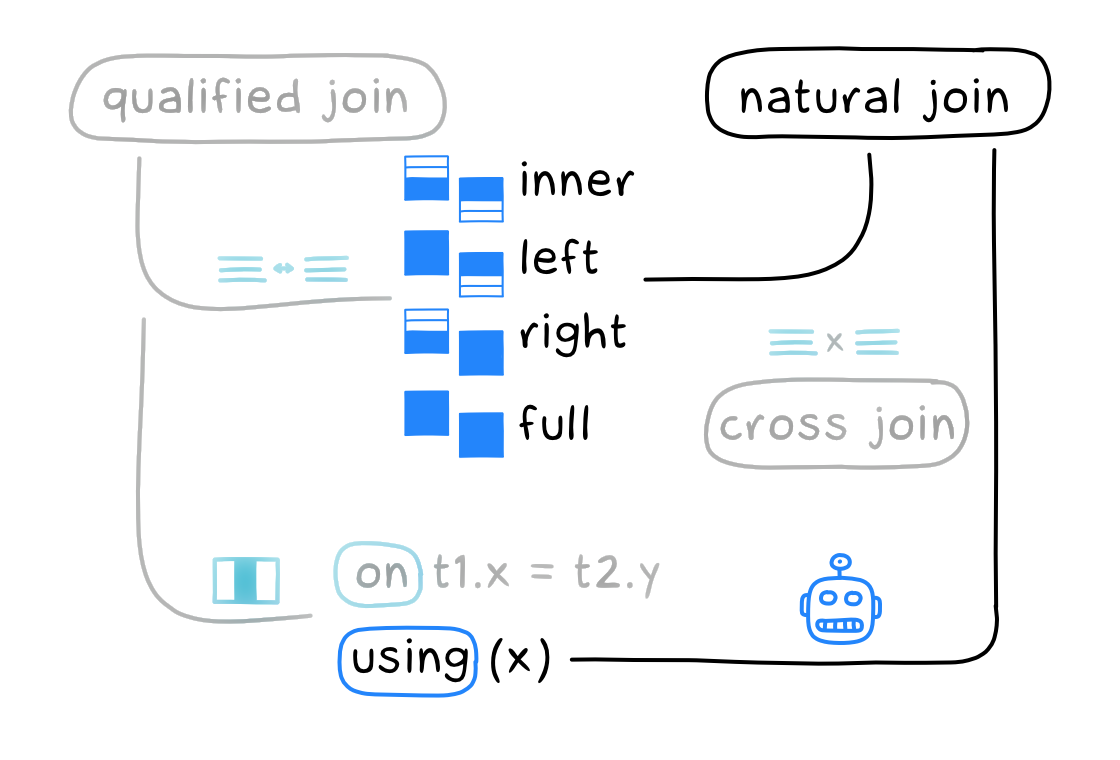

Natural join

A natural join is like a qualified join with using, except that we don't specify matching column names at all:

select

job_name, comp_name

from jobs

natural join companies;

A natural join finds all pairs of columns with the same name and uses them as join criteria.

Similar to using, a natural join only checks for equality. And just like a qualified join, a natural join can be either inner (default), left, right, or full:

table NATURAL [join-type] JOIN table

Using natural joins is almost always a bad idea. Imagine we have a name column in both tables:

create table jobs (

job_id integer primary key,

comp_id integer,

name text

);

create table if not exists companies (

comp_id integer primary key,

name text

);

Completely valid design. However, a natural join between jobs and companies would return an empty result, because it implicitly matches on the following condition:

jobs.comp_id = companies.comp_id and jobs.name = companies.name

So I'd take qualified join with using over natural join any day.

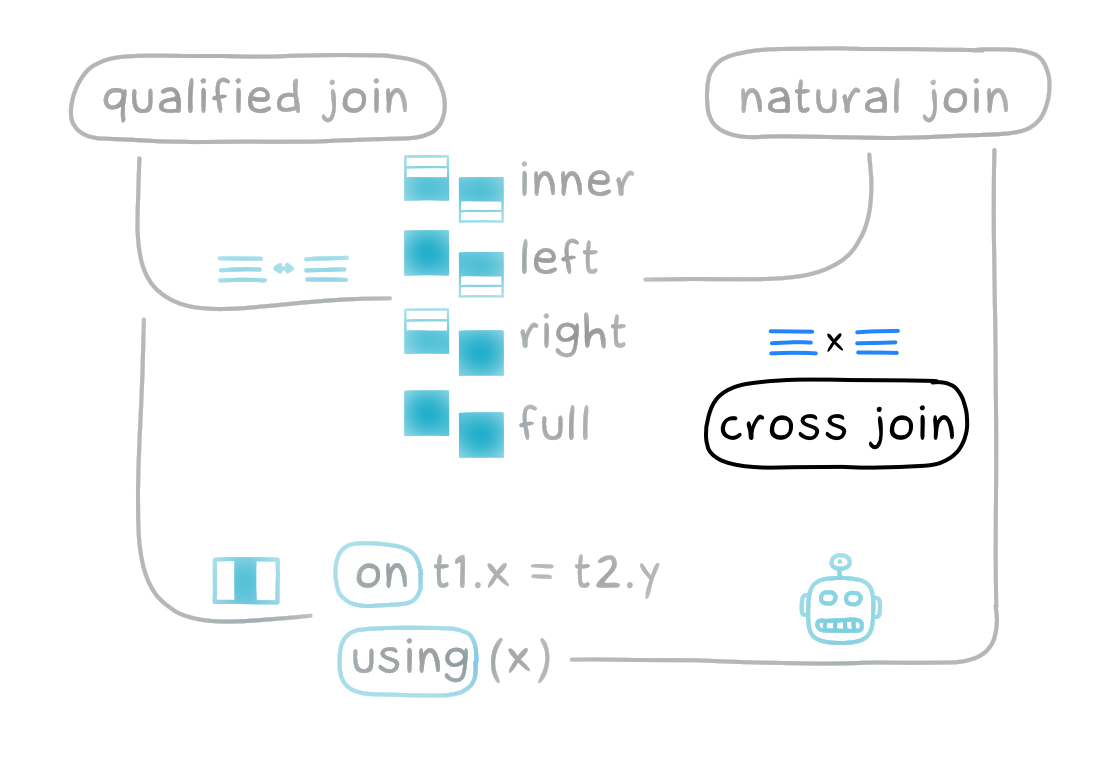

Cross join

The third and final variation of join is a cross join, also known as a Cartesian join:

select

job_name, comp_name

from jobs

cross join companies;

A cross join completely ignores column values. It joins every row from the left table (N rows) with every row from the right table (M rows), resulting in N×M rows.

A cross join can be useful if you need to generate all pairs of values from two tables, such as all "size-color" combinations for a product. Not so useful in our jobs example, I suppose.

A cross join is equivalent to an inner join without matching criteria:

select

job_name, comp_name

from jobs

join companies on true;

Sometimes you will see a cross join written this way:

select job_name, comp_name

from jobs, companies;

While this query doesn't use the join keyword at all, it is exactly the same cross join.

Partitioned join

Didn't I say earlier that there are only three variations of joins — qualified join, cross join, and natural join? Well, yes.

But here is a thing. Remember our qualified join specification?

table [join-type] JOIN table join-specification

According to the SQL standard, the table here can be a partitioned join table (not related to table partitioning in any way!):

select ...

from table_x partition by (col_1, col_2, ...)

join table_y on ...

;

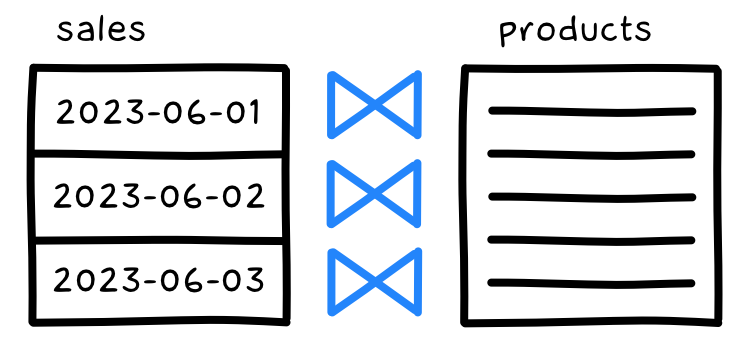

Let's say we have products and their sales over time:

sales products

┌────┬────────────┬────────────┬──────────┐ ┌────┬───────┐

│ id │ sale_dt │ product_id │ quantity │ │ id │ name │

├────┼────────────┼────────────┼──────────┤ ├────┼───────┤

│ 1 │ 2023-06-01 │ 10 │ 30 │ │ 10 │ Alpha │

│ 2 │ 2023-06-01 │ 20 │ 60 │ │ 20 │ Beta │

│ 3 │ 2023-06-01 │ 30 │ 90 │ │ 30 │ Gamma │

│ 4 │ 2023-06-02 │ 20 │ 60 │ └────┴───────┘

│ 5 │ 2023-06-03 │ 10 │ 30 │

│ 6 │ 2023-06-03 │ 30 │ 90 │

└────┴────────────┴────────────┴──────────┘

(swipe left to see the products)

Let's select sales with corresponding product names:

select

sale_dt, products.name, quantity

from sales

join products on sales.product_id = products.id

order by sale_dt;

So far so good. But what I'd like to see here is how each of the products performed on each day (when there was at least one sale). Including zero sales for some of the products:

┌────────────┬───────┬──────────┐

│ sale_dt │ name │ quantity │

├────────────┼───────┼──────────┤

│ 2023-06-01 │ Alpha │ 30 │

│ 2023-06-01 │ Beta │ 60 │

│ 2023-06-01 │ Gamma │ 90 │

│ 2023-06-02 │ Alpha │ 0 │

│ 2023-06-02 │ Beta │ 60 │

│ 2023-06-02 │ Gamma │ 0 │

│ 2023-06-03 │ Alpha │ 30 │

│ 2023-06-03 │ Beta │ 0 │

│ 2023-06-03 │ Gamma │ 90 │

└────────────┴───────┴──────────┘

There is no way I can accomplish this without additional tricks. Unless I use a partitioned join.

A partitioned join tells the database engine to perform the join independently within each of the partitions we have defined for a table. So if we partition sales by date:

select

sale_dt, name, quantity

from sales partition by (sale_dt)

right join products on sales.product_id = products.id

order by sale_dt, name;

Then the database engine will independently join sales and products for 2023-06-01, then for 2023-06-02, then for 2023-06-03, and finally union the results. This will give us the exact result we wanted (except for nulls instead of zeros):

┌────────────┬───────┬──────────┐

│ sale_dt │ name │ quantity │

├────────────┼───────┼──────────┤

│ 2023-06-01 │ Alpha │ 30 │

│ 2023-06-01 │ Beta │ 60 │

│ 2023-06-01 │ Gamma │ 90 │

│ 2023-06-02 │ Alpha │ (null) │

│ 2023-06-02 │ Beta │ 60 │

│ 2023-06-02 │ Gamma │ (null) │

│ 2023-06-03 │ Alpha │ 30 │

│ 2023-06-03 │ Beta │ (null) │

│ 2023-06-03 │ Gamma │ 90 │

└────────────┴───────┴──────────┘

I have to say that this is a rather strange feature. I'm surprised it's in the standard at all (probably something to do with Oracle having it). Other vendors besides Oracle have never implemented partitioned joins, and I can't blame them.

Anyway, I just wanted you to know about it so you could share my burden of unnecessary SQL knowledge.

In case you were wondering (I know you weren't), here's how to solve the problem without partitioned joins:

-- select distinct dates

with dates as (

select distinct sale_dt

from sales

)

-- cross join dates with products

-- to get all the date-product pairs,

-- then join them with sales data

select

dates.sale_dt,

name, quantity

from dates

cross join products

left join sales on sales.sale_dt = dates.sale_dt

and sales.product_id = products.id

order by dates.sale_dt, name;

Easy-peasy.

Lateral join

SQL is a strange beast. While the standard includes the partitioned join (which no one but Oracle supports), it also contains a more powerful and widely supported lateral join.

A lateral join (as opposed to a traditional join) allows you to use correlated subqueries. We'll see what that means in a moment.

sales products

┌────┬────────────┬────────────┬──────────┐ ┌────┬───────┐

│ id │ sale_dt │ product_id │ quantity │ │ id │ name │

├────┼────────────┼────────────┼──────────┤ ├────┼───────┤

│ 1 │ 2023-06-01 │ 10 │ 30 │ │ 10 │ Alpha │

│ 2 │ 2023-06-01 │ 20 │ 60 │ │ 20 │ Beta │

│ 3 │ 2023-06-01 │ 30 │ 90 │ │ 30 │ Gamma │

│ 4 │ 2023-06-02 │ 20 │ 60 │ └────┴───────┘

│ 5 │ 2023-06-03 │ 10 │ 30 │

│ 6 │ 2023-06-03 │ 30 │ 90 │

└────┴────────────┴────────────┴──────────┘

(swipe left to see the products)

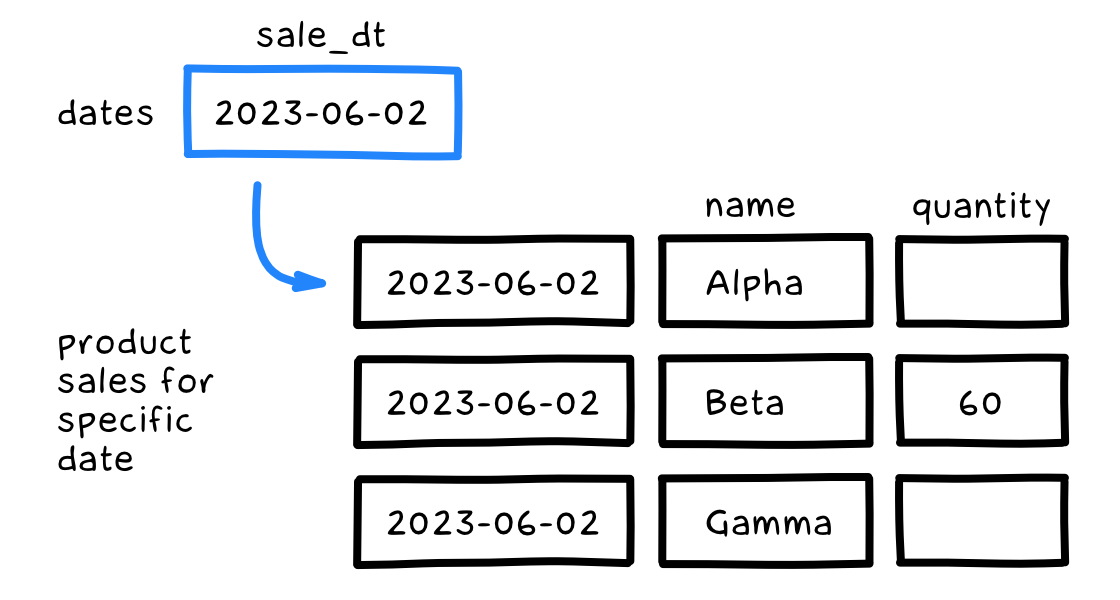

Let's go back to our products/sales example and see how each product sold on June 2nd:

select

'2023-06-02' as sale_dt, name, sales.quantity

from products

left join sales on products.id = sales.product_id

and sales.sale_dt = '2023-06-02';

Now let's say we want to see product sales for all days (just like we did with the partitioned join). It would be nice to select distinct dates with a subquery and join it with the product/sales subquery from above:

select

d.sale_dt, ps.name, ps.quantity

from

(select distinct sale_dt from sales) as d

join (

select d.sale_dt, name, sales.quantity

from products

left join sales on products.id = sales.product_id

and sales.sale_dt = d.sale_dt

) as ps on true

order by sale_dt, name;

Nah. We can't reference the sale_dt column provided by the preceding d subquery in the ps subquery. Unless we use a lateral join, which allows just that:

select

d.sale_dt, ps.name, ps.quantity

from

(select distinct sale_dt from sales) as d

join lateral (

select d.sale_dt, name, sales.quantity

from products

left join sales on products.id = sales.product_id

and sales.sale_dt = d.sale_dt

) as ps on true

order by sale_dt, name;

The d subquery selects the dates, while the ps subquery joins with it on the sale_dt column to select the product sales for that date. All thanks to the lateral join. Nice!

You may be wondering about the on true join condition. Thing is, the actual join on sale_dt already happens inside the ps subquery, so we don't need to repeat it outside. Try changing on true to d.sale_dt = ps.sale_dt and see that nothing changes.

Lateral joins are supported by PostgreSQL, MySQL and Oracle. MS SQL Server does not support them per se, but provides the same functionality with cross apply (= join lateral) and outer apply (= left join lateral) syntax.

Summary

There are three variations of joins defined in the SQL standard:

- qualified join (= using specific match critera),

- natural join (= automatic match critera),

- cross join (= inner join with no specific match critera).

A qualified join comes in four types: inner, left, right, and full.

It also provides on and using flavors of matching criteria.

Most vendors support them all, with the notable exception of MS SQL Server, which doesn't know anything about using and natural joins.

There are also table modifiers that change the join behavior:

lateral, supported by PostgreSQL, MySQL and Oracle (and MS SQL Server with a different syntax). It allows correlated subqueries in thejoinpart of the query.partition by, supported by Oracle only. It performs the join independently within each of the defined partitions.

Oh, and MySQL doesn't support full joins. Just because.

That's it!

──

P.S. Interested in mastering advanced SQL? Check out my book — SQL Window Functions Explained

★ Subscribe to keep up with new posts.